The University of California, Riverside, writes on their website about a study done in collaboration with the University of Delaware, published in Nature Food. In a two-step process, the study converted carbon dioxide, water, and electricity into acetate, one of the main ingredients in vinegar. Organisms have then been able to absorb the acetate in the dark and grow, without the intervention of natural photosynthesis.

Organic photosynthesis, through which plants grow naturally, is incredibly inefficient as only 1 percent of the energy that comes from sunlight ends up in the plant. With the new hybrid method of an organic-artificial system, yeast can be developed with 18 times higher efficiency than naturally, while algae can be grown with 4 times higher efficiency.

“With our method, we sought to identify a new way of producing food that can go beyond the limits that usually exist with biological photosynthesis”, says Robert Jinkerson, one of the study's co-authors.

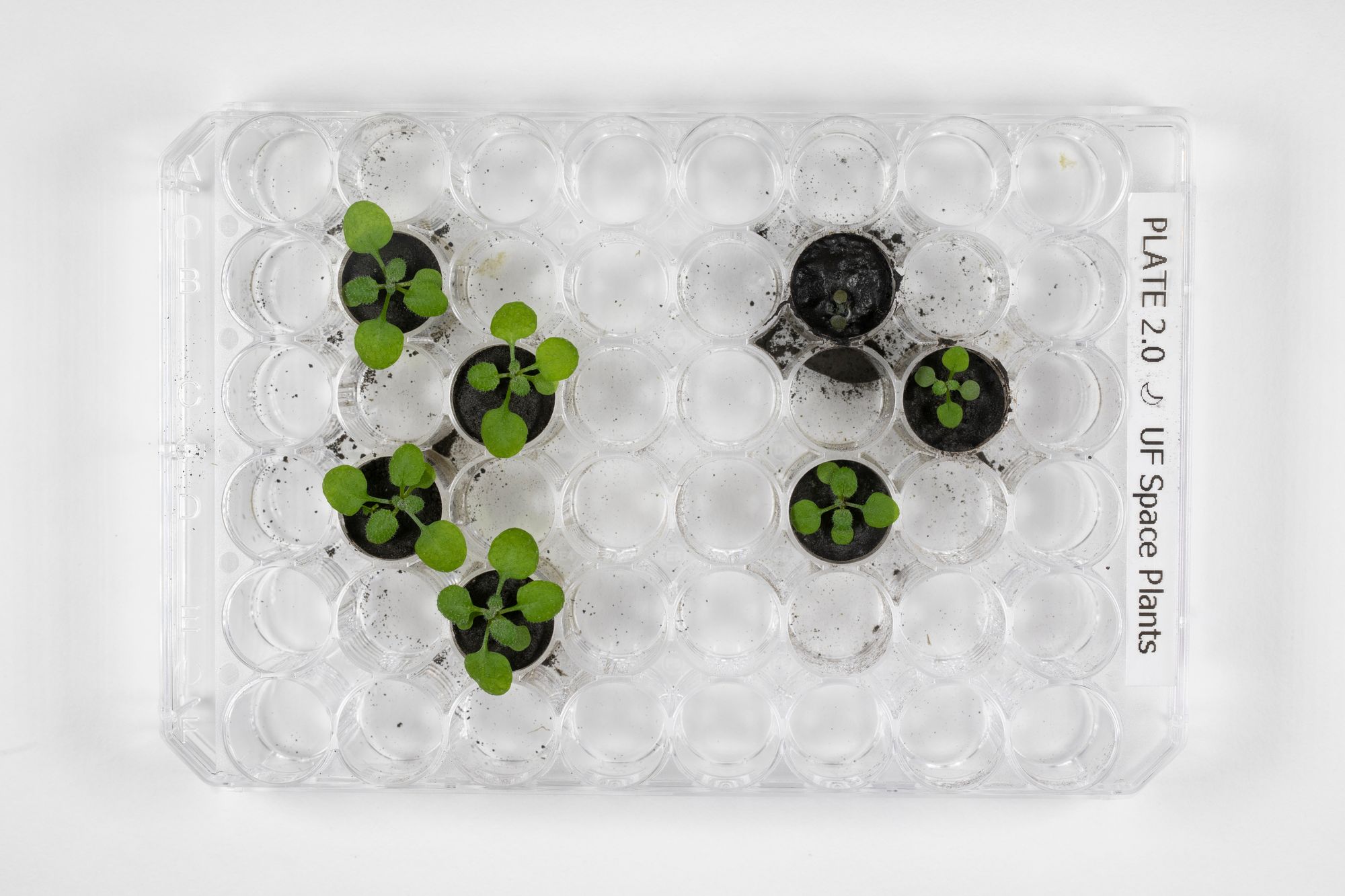

In addition to yeast and algae, the researchers have succeeded in growing rice, tomatoes, and peas, among other things, using the method.

“We found that a wide range of crops can absorb the acetate that we provide and incorporate it into the large molecular building blocks that the organism needs to grow and thrive. With some farming and engineering that we are now working on, we might be able to cultivate with acetate as an extra energy source and get bigger harvests”, says Marcus Garland-Dunaway, one of the main authors of the study.

Opening many doors

By freeing cultivation from dependence on sunshine, many possibilities open up; such as growing under more difficult conditions that may result from climate change, allowing a smaller amount of land to be taken up by agriculture, or being able to grow food during space travel – on the space shuttle itself or on a celestial body with less sunlight than we have on Earth.

“The use of methods with artificial photosynthesis can be a paradigm shift in the way we feed humans. By increasing the efficiency of food production, less land mass is required, reducing agriculture's impact on the environment. And for agriculture that takes place in less traditional environments, such as outer space, the increased energy efficiency can help feed more passengers with less input”, Jinkerson continues.

The cultivation method was submitted to NASA's Deep Space Food Challenge, where it was named one of the winners in Phase 1. The Challenge is an international competition for methods of producing food that requires minimal input, but which maximizes safe, nutritious, and tasty food for long space missions.

“Imagine giant ships growing tomatoes on Mars in the dark – how much easier wouldn’t that make it for the Martians?” concludes Martha Orozco-Cárdernas, one of the co-authors of the study.