Åtvidaberg is a tiny Swedish town with 7,000 inhabitants. In the summer of 1966 Edson Arantes do Nascimento walked the streets of Åtvidaberg. Better known as Pelé, by many regarded as the best football player of all time. The Brazilian national football team had their training camp there before the FIFA World Cup in England.

How did they end up spending three weeks in Åtvidaberg? Well, that was what everyone also wondered.

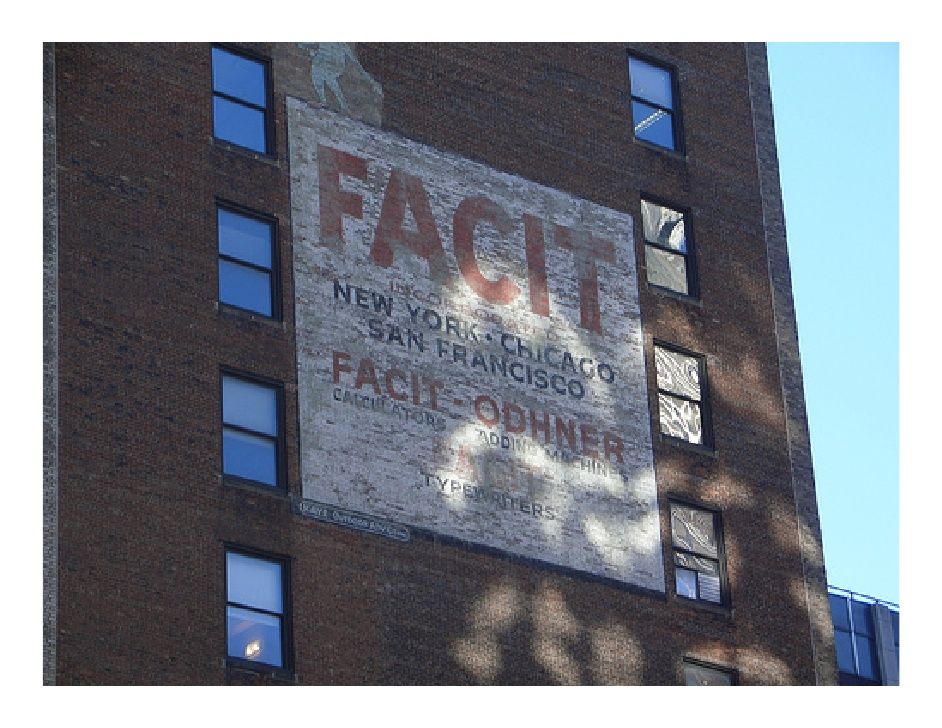

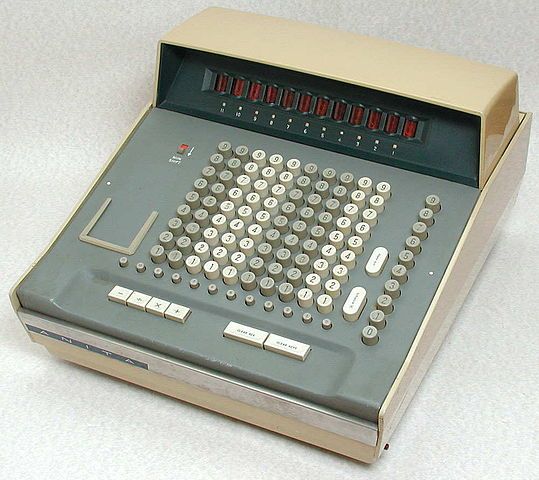

The answer lies in a local Åtvidaberg company, Facit, that in 1966 was close to its peak. Just a few years after the Pelé visit, they employed 14,000 people in 140 countries. Bringing Brazil’s national football team there was perfect worldwide marketing for their biggest product: mechanical calculators.

Just six years later the company was fighting for its life in what has been known as the Facit crisis. A new product had emerged that swept away the market for Facit’s products: electronic calculators.

How could they’ve been so stupid?

People have been asking themselves ever since: How could they have been caught unaware of the impact of electronic calculators?

The irony is that the company name, Facit, means ‘answer’ or ‘solution.’ Facit went under because they didn’t know the answer and couldn’t find a solution.

For decades people have marveled over their stupidity, but lately researchers have dug into company documents and revealed a more complicated story. Facit actually understood that a big change was coming, but they missed when it was coming.

For a short while in the 1950s the world’s fastest supercomputer was found in Sweden. It was called BESK (bitter in English, so many ironic names!) Binary Electronic Sequence Calculator.

In 1956 Facit recruited the people that built that computer, and strengthened its image as a cutting-edge and technology-oriented company. They founded Facit Electronics and tried to become the IBM of Scandinavia making mainframe computers, but only sold eleven computers and soon gave up. The endeavor had strengthened their belief in research and development and in 1962 it created an R&D division.

During the rest of the 1960s it became increasingly clear to the company that electronic calculators were the future, but Facit’s profits still lay in the mechanical calculators. The company was also divided over when the electronic calculators would have its big breakthrough.

Fooled by an exponential growth

The whole company lived in a linear world. The progress for mechanical calculators was slow and evolutionary, not exponential. And the peril of exponential growth is that it at first looks really slow. In 1961 the smallest electronic calculator covered a whole desk and cost $20,000. Who would have thought that it only ten years later would fit in a pocket and cost 98 percent less? Most likely Facit was fooled by this exponential growth.

Before the coronavirus pandemic I used to tell stories of Indian emperors, rice and chess boards to explain exponential growth. Now you just need to mention the spread of a virus and everyone gets it. From one person to two, to four, eight, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256 – 20 doublings later you have one million infected people. And just ten doublings after that you have one billion infected.

Moore’s law

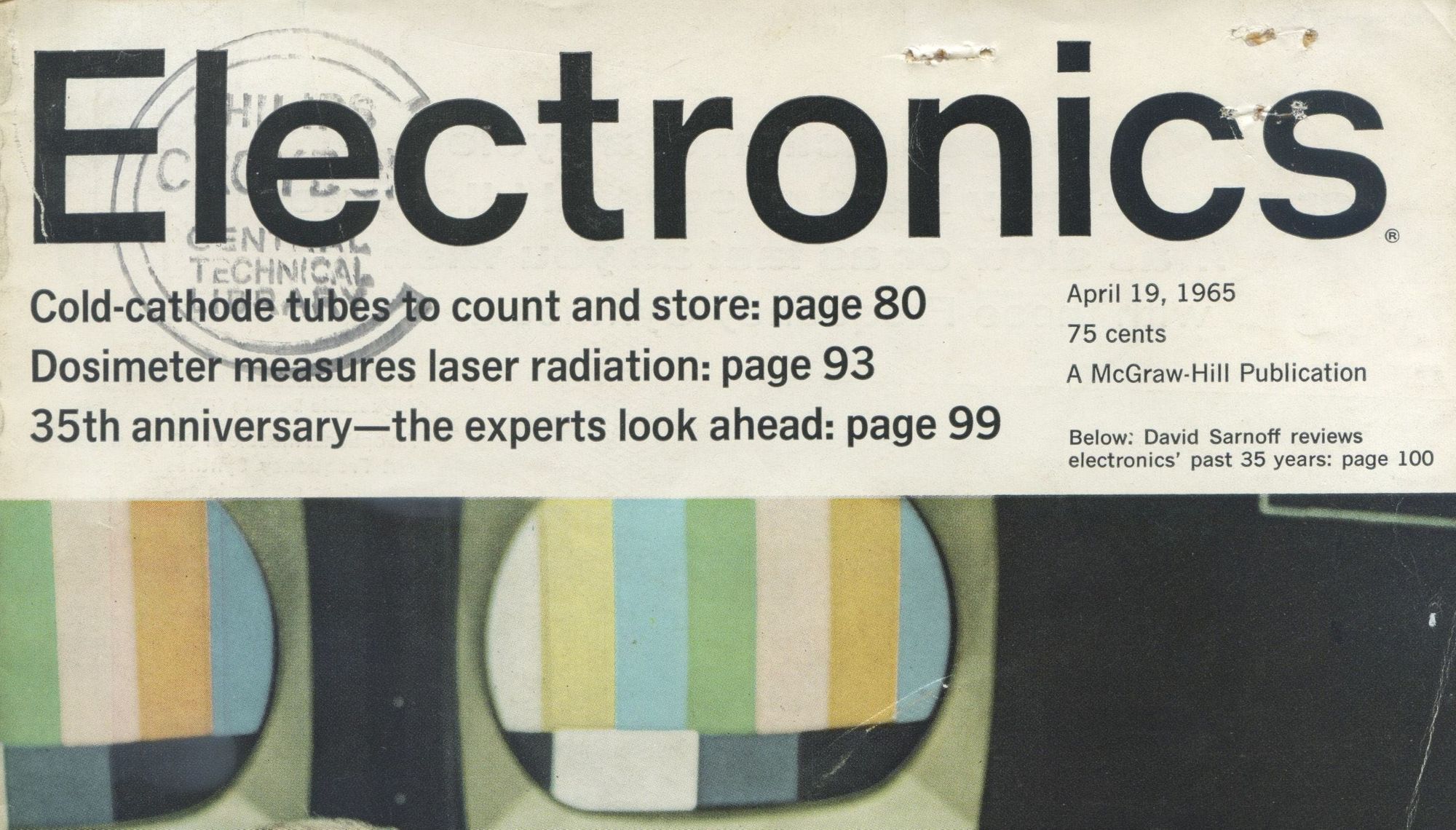

It probably would have helped if people at Facit had read the 1965 April edition of the magazine Electronics. In it Gordon Moore described what has become known as Moore’s law.

In the article he showed that the number of transistors in an integrated circuit had doubled every year from 1959 to 1965, from one to 65, without the cost per circuit increasing. He also predicted that the doubling would continue for at least ten more years. That would mean 65,000 transistors per circuit in 1975. The actual number in 1975 was 65,536.

(I’ve written before about Moore’s law, you can find it here.)

This exponential growth powered the rise of the electronic calculators and made them into cheap pocket calculators.

From top till bottom in two years

The same exponential growth took Facit from a successful global company to nothing. In 1971 it peaked with 14,000 employees, and in 1973 it, in reality, stopped existing when it was sold to Electrolux.

In the late 1960s the company spent considerable time figuring out how and when to make the transition. They wanted to keep the profits from the mechanical calculators as long as possible. Some people in the organization said the big shift would occur in 1971 and 1972, which turned out to be exactly right. Others thought it would take much longer. So they waited and kept a close watch.

You can’t just wait for the future

This was obviously the wrong decision. When the shift came there wasn’t enough time for Facit to make the transition. They probably should have gone all-in in the early 1960s and used their profits to develop an electronic calculator. If successful, Facit could still be around as an even bigger multinational company. And maybe Messi would have walked the streets of Åtvidaberg.

The lesson from the Facit story is this: It is better to create the future than to wait for the future.

Mathias Sundin