What important truth do very few people agree with you on?

This question, posed by Peter Thiel in his book Zero to One, is hard to answer. You need to understand something about the world that most people don’t.

If you can answer it, there lies tremendous opportunity. A great invention or revolutionary idea is rare; otherwise it wouldn’t be an important truth that few people agree with you on.

To answer the question you can start with this one instead: What does everybody agree on?

Everybody, or at least a significant majority, thinks the world is getting worse. They believe extreme poverty is increasing, that people are getting poorer, very few children go to school and child mortality is high and increasing. If they learn that child mortality is decreasing, they worry about overpopulation.

Many people worry about new technology. That their kids will take harm by watching a screen, self-driving cars will be death traps or that Terminator is a documentary.

All of this is false, but most people agree that it is true. If you know the facts, your answer to the question “what important truth do very few people agree with you on?” could be:

I know that humanity overall is moving in the right direction and that the future will most likely be better than the present, and very much better than the past.

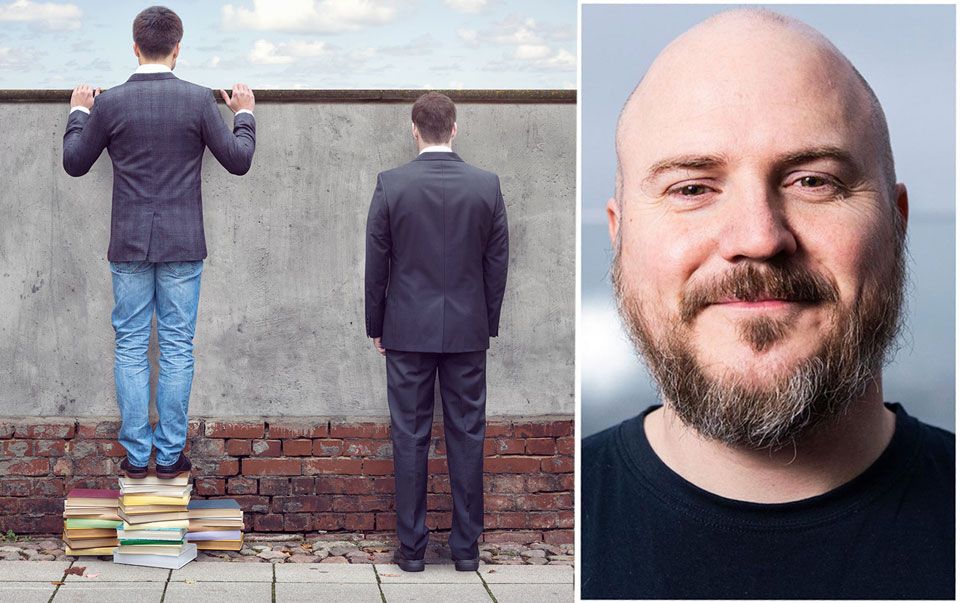

That gives you a platform to stand on when you look for opportunities. Betting on progress, human ingenuity and structured curiosity almost always come with positive returns.

With this basic understanding of the world, you can view whatever field or area and find the opportunities hidden in the prevailing pessimism.

The pessimist’s fallacy is to confuse a world getting more complex with one that is getting worse. The price of progress is indeed complexity, but this does not mean that the world is worse off – it just means that to navigate it you need better models and tools – and optimists can find those.

Pessimists settle for a simplistic model in which the trends all slope downward – a defeatist and wrong model that locks them into risk-minimization and retreat as their primary decision patterns. Optimists ride complexity, pessimist succumbs under it.

As fact-based optimists we look at the world as it is – but focus on the data that is being discounted by the pessimists.

When the world thinks things are getting worse, and they are getting better, the fact-based optimist has an undeniable edge.

The optimist’s edge.

Mathias Sundin

A great example of this is Peter Carlsson, founder of battery maker Northvolt.

Peter’s story teaches us two lessons:

You need to understand the future to see the possibilities, and you must be an optimist to grab them: Northvolt and the benefit of understanding the future.