One of the major problems with curing cancer is that there is so much variation among tumors. A treatment that works great for one patient may not work at all for another. But researchers at the University of Chicago Medicine have found a way to use nanotechnology to optimize the treatment of different types of tumor cells .

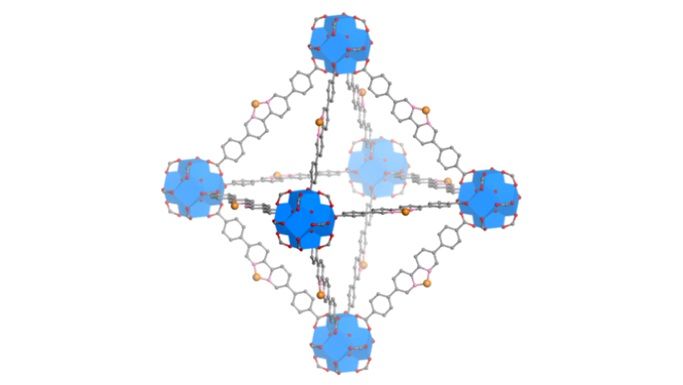

These are actually two methods that the researchers have combined to have the greatest possible effect. One method is called nanoscale Metal-Organic Frameworks , nMOF. It aims to create structures that are only a few nanometers in size and that are built of so-called photosensitizing materials.

This material generates large amounts of free radicals if irradiated. Free radicals are molecules that react easily with other substances in the body and that can cause great damage to cells, both healthy cells and cancer cells.

With the nMOF technology, it is possible to send quantities of the small structures to the area where there is a tumor. By then irradiating the area with X-rays, large amounts of free radicals are released which attack and destroy the tumor.

Radiation and medicine in one

But the tumor may have spread to places that are not irradiated and here the second part of the method comes in. The researchers have built the structure so that it can transport drugs that are also released when the structure is irradiated.

These drugs can be tailored to activate the immune system and make it react much more strongly to the antigens that identify the cancer to be fought. In animal experiments, it has been shown that the method is effective in both knocking out the local tumor and getting the immune system to find and destroy similar cancer cells elsewhere in the body.

The researchers will now go further and try to make the method even more efficient.

We are now refining the design of nMOF and its delivery of drugs ahead of our tests on humans. We are working hard to find the best variant so that we can use it in clinical trials that will hopefully start within two to three years or even earlier, says Ralph Weichselbaum, professor at the University of Chicago and one of the researchers behind the method.