The political landscape and mood in Sweden and other Western European countries are becoming increasingly similar. It is not news that many within what might be called the liberal elite express concern about the regressive and anti-democratic tendencies they see.

What do I mean by the liberal elite? The definition is not crystal clear, and part of the point of this column is that what is liberal changes over time.

But let's define it this way: The representatives of the political system and the media world who still feel that they stand for, if not a consensus, then at least a widely agreed narrative about how society at large should be run and what is important and less important. That is, the device that with an English term is usually called mainstream.

It matters less whether these representatives call themselves – and now I am referring to general Western concepts – social democrats, socialists, liberals, Christian Democrats, or conservatives.

Is something really about to break?

When you take part in situation descriptions from this mainstream, you can get the impression that something is about to break. Not infrequently it is formulated in approximately that way. And that does not only apply to Sweden, but to the entire so-called Western world.

I have no doubt that those who say so are genuinely concerned that something valuable that has been won is in danger of being lost. But it is in many ways a narrow way of describing what is going on.

Partly, everything changes all the time. That is the nature of existence.

Partly, it is not fair to unreflectively describe change (which is therefore constantly ongoing) as destructive. In that case, all previous social transformation has been destructive.

Partly – and here comes what probably surprises said 'elite' the most – the definitions of what is liberal, radical, conservative, and "extreme" (an overused term) shift so much over time that the labels would not be recognizable to a person from 60s or the 70s that visited our time – and the shift moves in a liberal direction. This is confirmed in research. (Those who attach a strong political charge to the term liberal can instead think of the direction as human rights.)

The liberal stance is gaining ground

The shift is too slow for debaters to notice, but over time it becomes very large.

Three years ago, a study was published in Nature Human Behaviour that describes how the attitudes on various valuation issues have changed over time in Sweden, Great Britain, and the United States. The conclusion was that the liberal stance is gaining ground in an almost relentless manner.

Views on homosexuality, equality, child abuse, and segregation are being liberalized particularly quickly. The positions are more fixed when it comes to abortion and euthanasia. There is an explanation for this:

The liberals, or progressives, are those who push for freedoms and rights of various kinds. The conservatives eventually follow, as a sort of drag anchor for society. But it is above all when the value arguments are about justice and about not harming that the conservatives allow themselves to be convinced. The latter would also be influenced by arguments about loyalty, authority, and purity, but since such things do not sway the liberal group, these arguments have no significance for how attitudes change in society at large.

For those who study trends, it is not difficult to find evidence that this is the case.

Immigration has increased, but not xenophobia

In the West, immigration has increased for decades without xenophobia increasing. It's the opposite. The view of equality, gay rights, violence as a conflict solver, and the causes of crime has shifted sharply in the direction of human rights.

Globally, the shift can be seen, among other things, in the World Values Survey's measurement series. In Sweden, it can be seen in the SOM institute's attitude surveys.

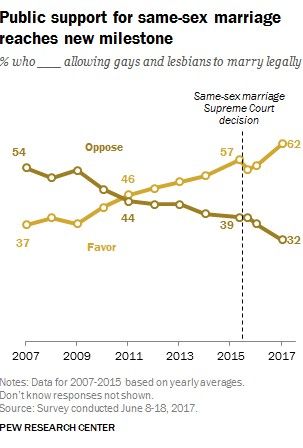

In the US, the Pew polling institute is a goldmine. There you can see, for example, that support for homosexuals' right to marry increased from 37 to 62 percent in just ten years. It also shows that the attitude towards immigration changed completely between 1994 and 2017 from two-thirds seeing it as a problem to two-thirds now seeing it as an asset.

Other surveys show that Americans' support for the death penalty is now at its lowest level to date (although it still appears high from the Swedish horizon).

Furthermore, the tendency towards the liberal (or human rights) side is also visible in countries where the starting point is significantly more conservative than in the West, such as Russia, Pontus Strimling, one of the researchers behind the study, told me when I interviewed him in 2019.

Today's conservatives are more liberal than yesterday's liberals

The shift in opinion that has taken place means that today's conservatives are more liberal than yesterday's liberals on many issues. An average Sweden Democrat voter today probably has roughly the same attitudes on matters of gender equality and sexuality as an average moderate or social democrat 20-30 years ago. Perhaps even in matters of immigration.

According to Strimling, the conservative parties that exist in 20 years will be less conservative than those that exist today, just as today's are less conservative than 20 years ago.

The Nature study has been described as groundbreaking. I consider it to be unequivocal evidence of progress. But it would be an exaggeration to claim that it made millions see the development with new, less anxious eyes. Every era has its references.

The differences between people with different political labels are small

Finally, a personal reflection: In what matters, that is, how you actually live your life, not what you write on Twitter, the differences between people with different political labels are small. Where there are differences, it can often be the case that the person who claims to be liberal in practice behaves less tolerant and more restricted than the person who claims to be conservative.

The opinions we point out as dividing lines between different political camps are largely about identifying ourselves with the camp where we feel at home for various social and cultural reasons. Discussions that end in disagreement are often built more on what we have learned to emphasize intellectually than on a genuine and honest description of how we actually relate to homosexuals, immigrants, or the opposite sex in real life.

Anders Bolling