One of the biggest challenges to overcome when travelling to Mars is the harsh radiation environment. Unlike here on Earth, there is no protective magnetic field there. Humans will be exposed to the radiation just like the spacecraft and rovers we send there, and it’s obviously not good for the health. Coming up with efficient solutions for radiation shielding is therefore a key requirement for deep space human spaceflight.

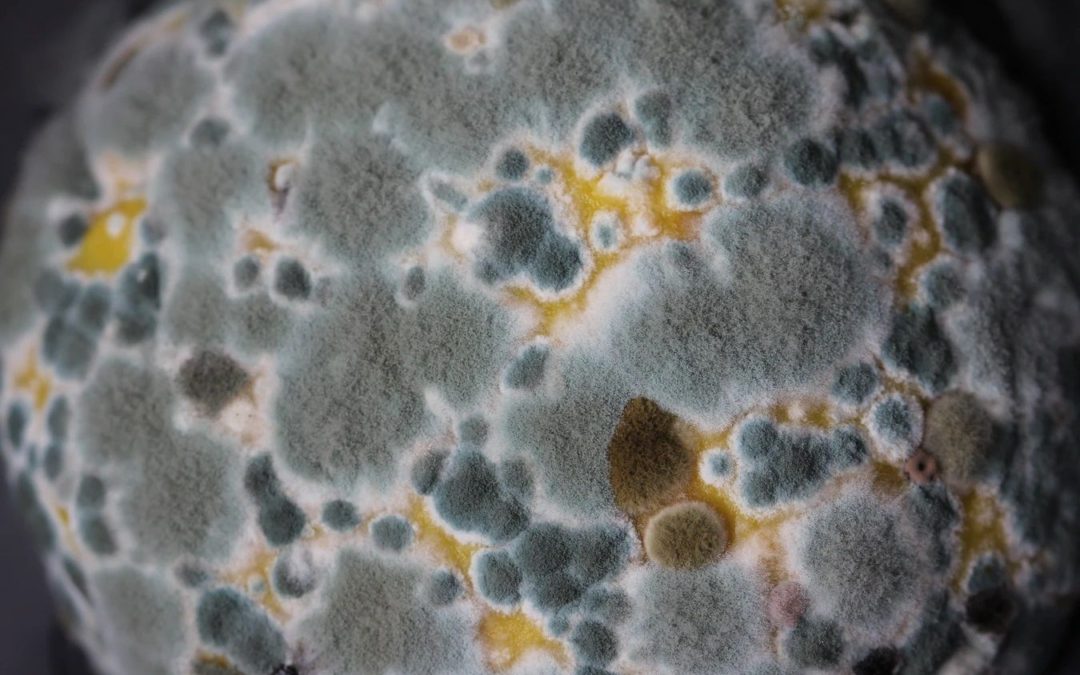

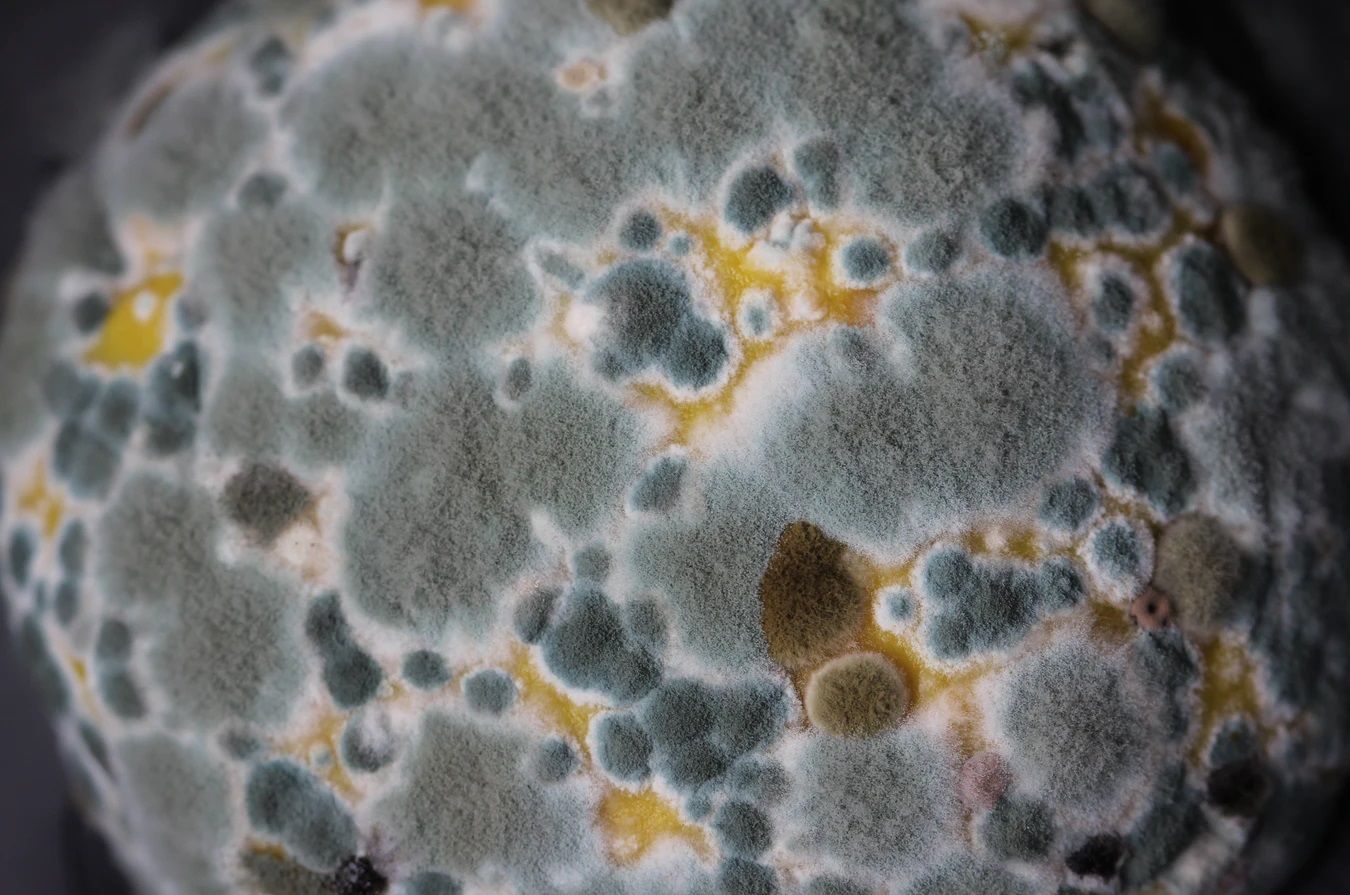

Scientists in the United States are now suggesting that radiotrophic fungi could be the solution. These are fungi that thrive in a radioactive environment. They can convert gamma-radiation into energy for themselves through a process known as radiosynthesis, analogous to photosynthesis on plants. They do this using a pigment called melanin. One such species is Cladosporium sphaerospermum. It had earlier been discovered that this fungus is thriving in the radiative environment at the abandoned Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine.

Samples of Cladosporium sphaerospermum were taken to the International Space Station in the winter of 2018-2019 to study the potential of the fungus being able to act as a low-cost and light-weight material for radiation shielding in a test environment that was designed to resemble conditions on Mars – with promising results! In a test where the radiation absorption of a fungus lawn of 1.7 mm in thickness was studied for 30 days, the findings yielded a radiation reduction by 2.17±0.35%. By estimation using a linear attenuation coefficient, this would correspond to roughly 21 cm of fungus wall being sufficient to cancel out an annual dose-equivalent of Mars’s radiation environment. Further study showed that using a mixture of melanin and the typical Martian regolith in equimolar proportions could reduce the required thickness to 9 cm.

A very useful feature of using radiotrophic fungi for radiation shielding is the light weight of the material, but also the low cost of getting it to Mars. If means of cultivating Cladosporium sphaerospermum on Mars would be developed, it would suffice to bring just a small amount of the fungus from Earth.

The study was published by researchers at Stanford University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.