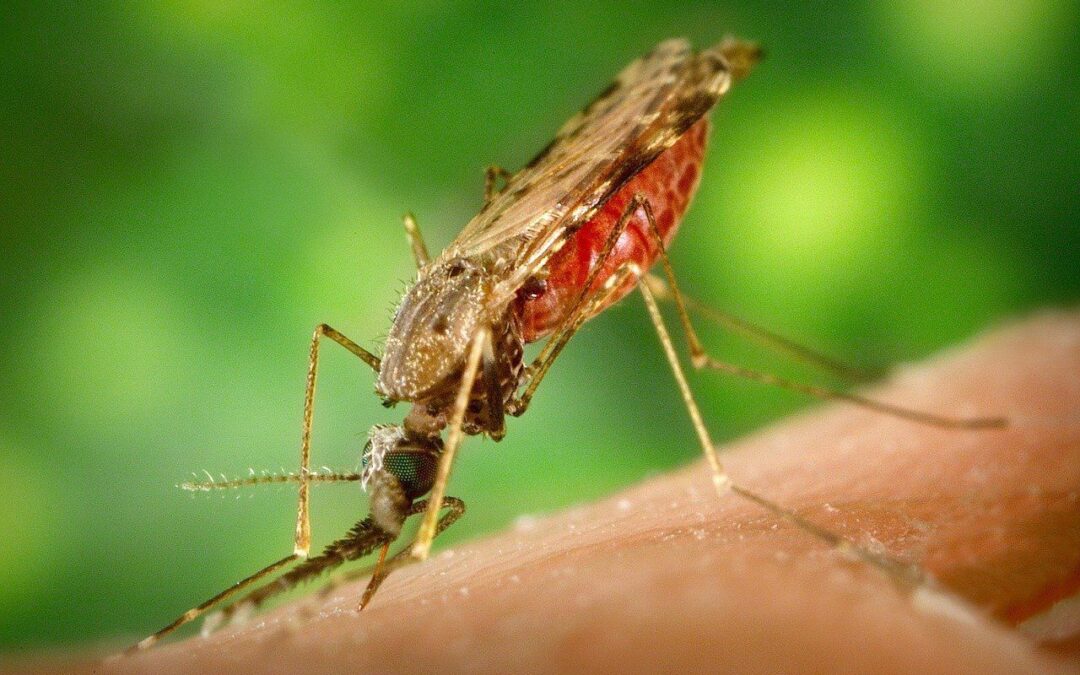

Researchers from the University of Oxford have tested a malaria vaccine, called R21, that works better than any of the vaccines we use today.

The WHO has set a goal that a vaccine must provide 75 percent protection for the parasite that spreads malaria to die out in the long run. The new vaccine provided 80 percent protection, which of course gives great hope for the future.

"If this vaccine is implemented at a large scale, it has the potential to change the world," says Katie Ewer, a professor at the University of Oxford and one of the researchers behind the study, in a comment to the BBC.

With the vaccine only costing a few dollars per dose, the researchers have high hopes that it will also really be rolled out to everyone who is in the danger zone.

Combined with mosquito nets and mosquito repellants, there is a chance that the new vaccine could completely stop malaria from spreading. It would then save the lives of 400,000 people, mostly children, every year around the world.

The researchers already received the first results from a study last year. But now they have analyzed the results a year later and can then see that the vaccine is just as effective even two years after the first vaccination. The parasite that spreads malaria thus does not seem to become immune to the new vaccine.

In the first trial, the researchers had 409 children test the vaccine. A larger phase III trial with 4,800 children is also underway, and if it shows the same results, the researchers hope to have the vaccine approved within a year. The world's largest vaccine manufacturer, the Serum Institute in India, says it is ready to produce 100 million doses a year of the vaccine as soon as it is approved. So we may soon see the beginning of the end of the malaria scourge.